Anscombe's quartert, variability and studying queues with Python

Anscombe’s quartet is a great example of the importance of fully understanding variability in a data set: it is a set of 4 data sets with the same summary measures (mean, std, etc…), the same correlation and the same regression line but with very different distributions. In this post I’ll show how easy it is to play with Anscombe’s quartet using Python and then talk about another mathematical area where variability must be fully understood: the study of queues. I’ll do this with the Ciw python library.

(If you would rather read this as jupyter notebook you can find it here: ipynb)

Here are all the imports that I’m going to need for this post:

>>> import pandas as pd # Data manipulation

>>> import ciw # The discrete event simulation library we will use to study queues

>>> import matplotlib.pyplot as plt # Plots

>>> import seaborn as sns # Powerful plots

>>> from scipy import stats # Linear regression

>>> import numpy as np # Quick summary statistics

>>> import tqdm # A progress bar

Anscombe’s quartet

First of all, let us get the data set, that’s immediate to do as it comes ready loadable within the seaborn library:

>>> anscombe = sns.load_dataset("anscombe")

We can see that there are 4 data sets each with different values of \(x\) and \(y\):

>>> anscombe

dataset x y

0 I 10.0 8.04

1 I 8.0 6.95

2 I 13.0 7.58

3 I 9.0 8.81

4 I 11.0 8.33

5 I 14.0 9.96

6 I 6.0 7.24

7 I 4.0 4.26

8 I 12.0 10.84

9 I 7.0 4.82

10 I 5.0 5.68

11 II 10.0 9.14

12 II 8.0 8.14

13 II 13.0 8.74

14 II 9.0 8.77

15 II 11.0 9.26

16 II 14.0 8.10

17 II 6.0 6.13

18 II 4.0 3.10

19 II 12.0 9.13

20 II 7.0 7.26

21 II 5.0 4.74

22 III 10.0 7.46

23 III 8.0 6.77

24 III 13.0 12.74

25 III 9.0 7.11

26 III 11.0 7.81

27 III 14.0 8.84

28 III 6.0 6.08

29 III 4.0 5.39

30 III 12.0 8.15

31 III 7.0 6.42

32 III 5.0 5.73

33 IV 8.0 6.58

34 IV 8.0 5.76

35 IV 8.0 7.71

36 IV 8.0 8.84

37 IV 8.0 8.47

38 IV 8.0 7.04

39 IV 8.0 5.25

40 IV 19.0 12.50

41 IV 8.0 5.56

42 IV 8.0 7.91

43 IV 8.0 6.89

Let us take a quick look at the summary measures:

>>> anscombe.groupby("dataset").describe()

x y

dataset

I count 11.000000 11.000000

mean 9.000000 7.500909

std 3.316625 2.031568

min 4.000000 4.260000

25% 6.500000 6.315000

50% 9.000000 7.580000

75% 11.500000 8.570000

max 14.000000 10.840000

II count 11.000000 11.000000

mean 9.000000 7.500909

std 3.316625 2.031657

min 4.000000 3.100000

25% 6.500000 6.695000

50% 9.000000 8.140000

75% 11.500000 8.950000

max 14.000000 9.260000

III count 11.000000 11.000000

mean 9.000000 7.500000

std 3.316625 2.030424

min 4.000000 5.390000

25% 6.500000 6.250000

50% 9.000000 7.110000

75% 11.500000 7.980000

max 14.000000 12.740000

IV count 11.000000 11.000000

mean 9.000000 7.500909

std 3.316625 2.030579

min 8.000000 5.250000

25% 8.000000 6.170000

50% 8.000000 7.040000

75% 8.000000 8.190000

max 19.000000 12.500000

We see that the summary statistics are, if not the same (a mean in \(x\) of 9, in \(y\) of 7.5) very similar. We can also take a look at the relationship between \(x\) and \(y\) in each data set by computing the regression line and visualising it:

>>> for data_set in anscombe.dataset.unique():

... df = anscombe.query("dataset == '{}'".format(data_set))

... slope, intercept, r_val, p_val, slope_std_error = stats.linregress(x=df.x, y=df.y)

... sns.lmplot(x="x", y="y", data=df);

... plt.title("Data set {}: y={:.2f}x+{:.2f} (p: {:.2f}, R^2: {:.2f})".format(data_set, slope, intercept, p_val, r_val))

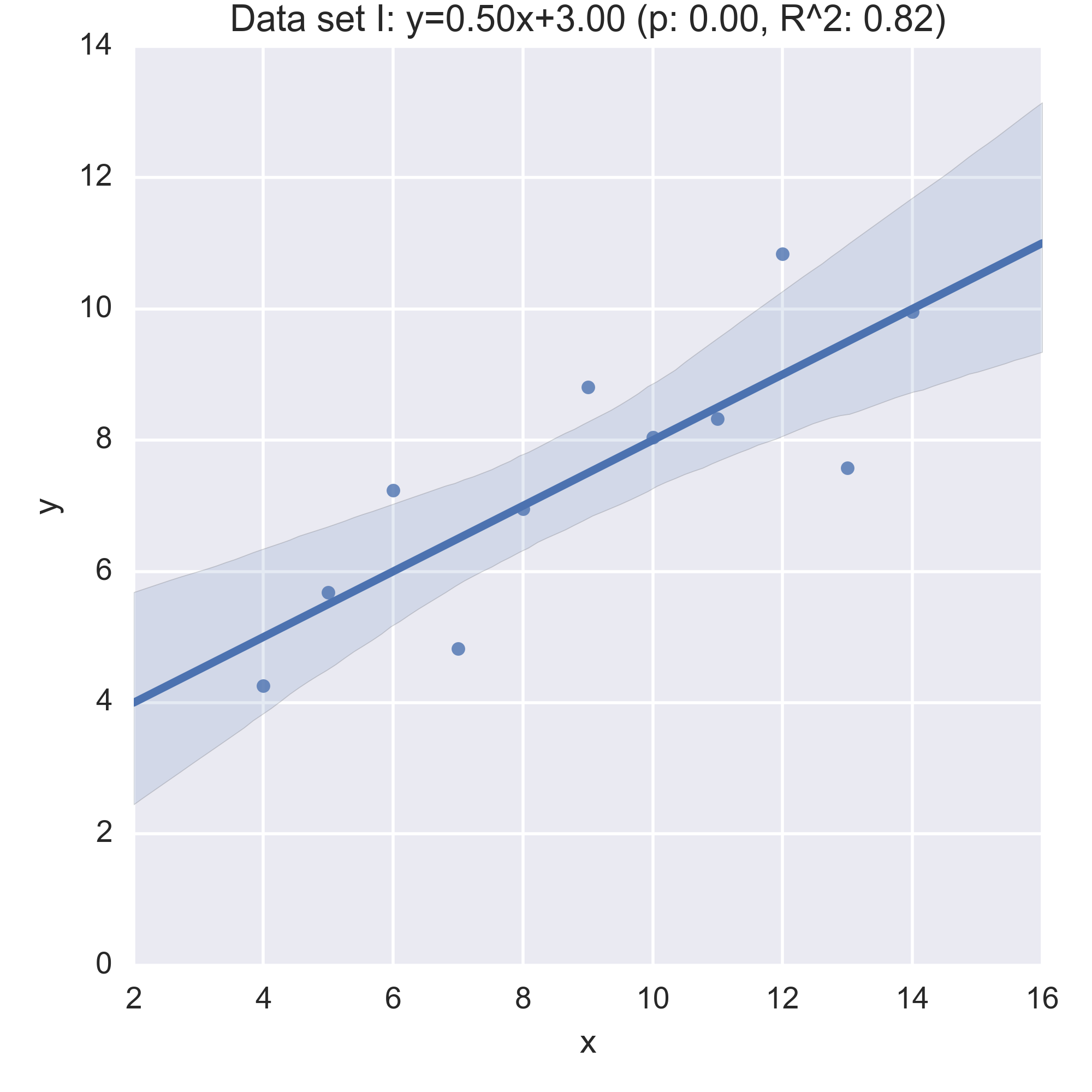

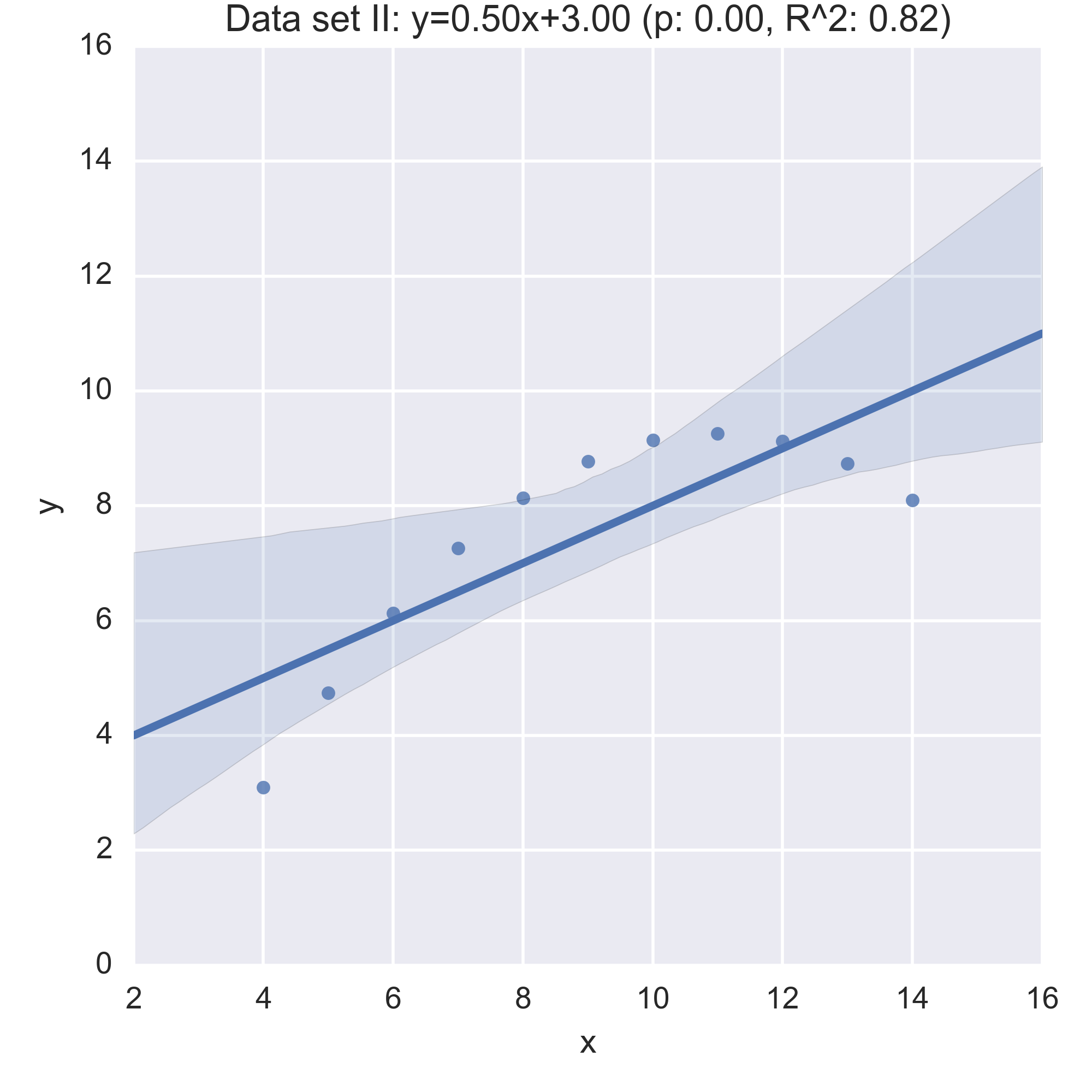

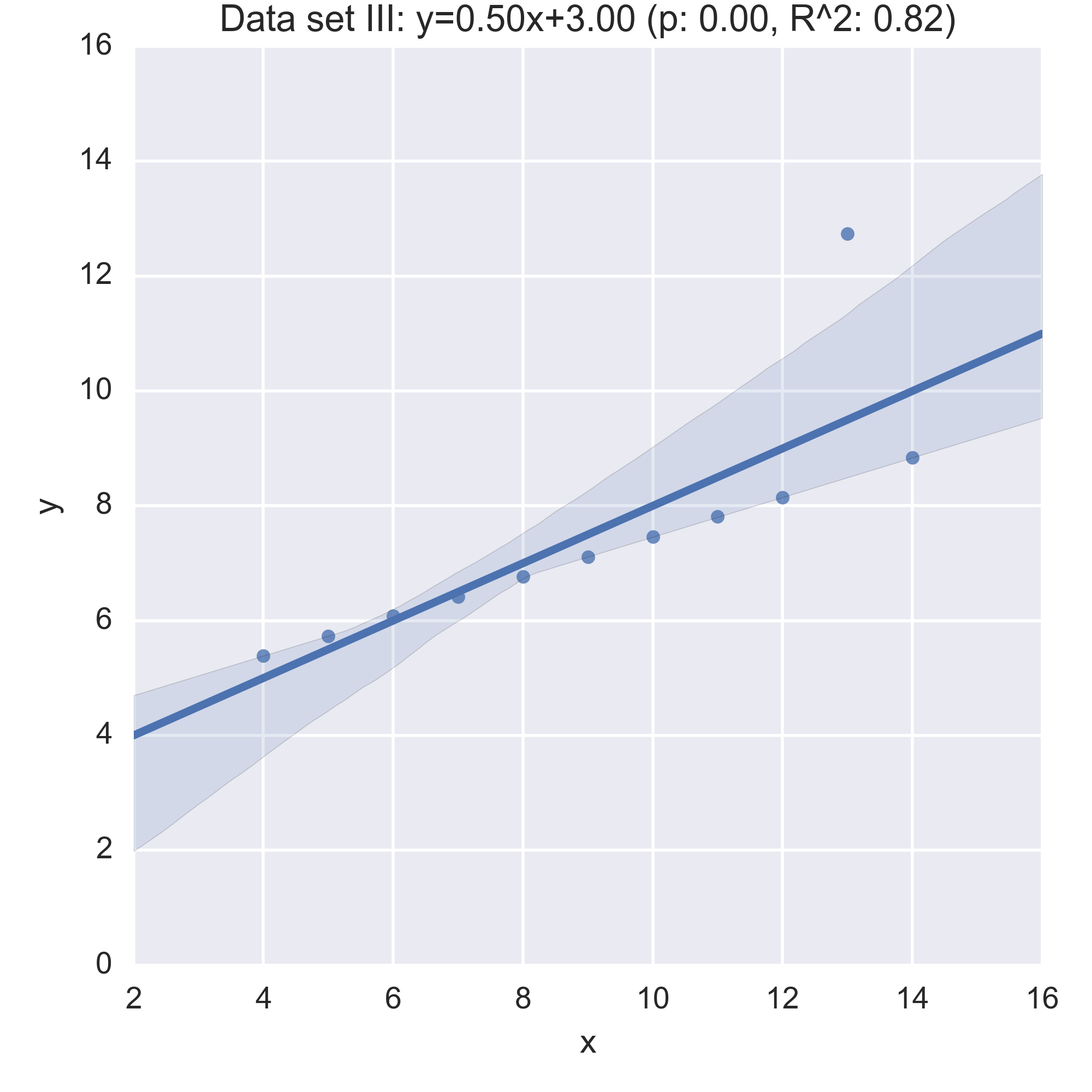

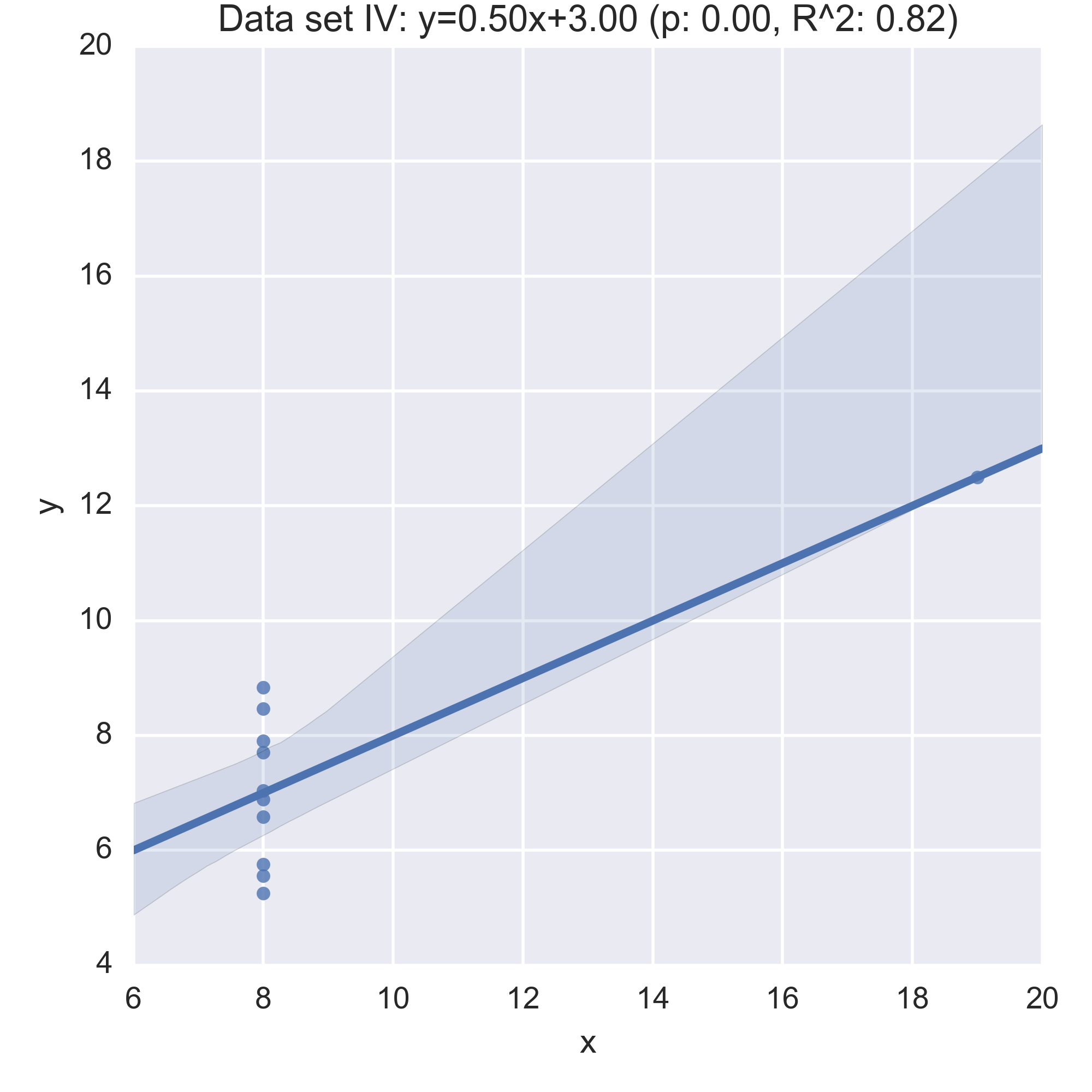

While the plots show that each data set is evidently different, they also all have the same regression line (with the same \(p, R^2\) values!):

Anscombe’s quartet is often used as an example justifying that a summary of a data set will inherently lose information and so should be accompanied by further study/understanding (such as in this case: viewing the plots of the data). (There even a paper out there showing how to generate similar data sets (behind a paywall): “Generating Data with Identical Statistics but Dissimilar Graphics: A Follow up to the Anscombe Dataset”)

Variability in queues

Another area of mathematics where it is imperative to have a good understanding of variability is queueing theory which is (suprise suprise) the study of queues. I’ve written about queueing theory before: here is a post about calculating the expected wait in a tandem queue, the main idea however is to assume some (random) distribution for the time between arrivals of individuals at a queueing system and another (random) distribution for the time it takes to “service” each individual.

When studied analytically these are often studied as Markov chains. The wikipedia entry for a single server queue wikipedia.org/wiki/Queueing_theory#Example_of_M.2FM.2F1 shows a picture for the corresponding chain.

These Markov models of queues assume that the distributions (of inter arrival times and service times) are Markovian: ie correspond to exponential distributions. This is often a good distribution that models realistic situations, however it is just as often not realistic. For example in healthcare systems such as hospital wards (which are just queues) service time distributions often follow a lognormal distribution.

When studying queues, as well as building analytical models it is possible to simulate the process using pseudo random number generators. One piece of software (the main developer being Geraint Palmer who is studying for his PhD with Paul Harper and I) that allows for this is ciw (the name is Welsh for queue! :)).

What I’ll do in the rest of this post is build a simulation model of a single server queue with ciw where individuals:

- Arrive on average according to a rate of .5 per time unit (so 2 time units between arrivals);

- Are served on average at a rate of 1 per time unit (so 1 time unit per service).

To do this in ciw we need to set up a parameters dictionary. Ciw is written so

as to handle most queueing systems but with queueing networks in mind in

particular and also the ability to handle multiple classes of individuals. In

our system we will just have one class of individuals Class 0 and the

transition matrix is a bit redundant because we’re dealing with a single queue.

Here is the dictionary for our system when assuming exponential distributions:

>>> parameters = {'Arrival_distributions': {'Class 0': [['Exponential', 0.5]]},

... 'Service_distributions': {'Class 0': [['Exponential', 1]]},

... 'Transition_matrices': {'Class 0': [[0.0]]},

... 'Number_of_servers': [1]}

Here is a function to run a single simulation:

>>> def iteration(parameters, maxtime=250, warmup=50):

... """

... Run a single iteration of the simulation and

... return the times spent waiting for service

... as well as the service times

... """

... N = ciw.create_network(parameters)

... Q = ciw.Simulation(N)

... Q.simulate_until_max_time(maxtime)

... records = [r for r in Q.get_all_records() if r.arrival_date > warmup]

... waits = [r.waiting_time for r in records]

... service_times = [r.service_time for r in records]

... n = len(waits)

... return waits, service_times

Here is a function to run a trial consisting of multiple runs of the simulation. This is important to help smooth the stochasticity of the random process.

>>> def trials(parameters, repetitions=30, maxtime=2000, warmup=250):

... """Repeat out simulation over a number of trials"""

... waits = []

... service_times = []

... for seed in tqdm.trange(repetitions): # tqdm gives us a nice progress bar

... ciw.seed(seed)

... wait, service_time = iteration(parameters, maxtime=maxtime, warmup=warmup)

... waits.extend(wait)

... service_times.extend(service_time)

... return waits, service_times

Let’s run a trial of the default parameters:

>>> waits, service_times = trials(parameters)

First, let us verify that we are getting the expected service time (recall it should be 1 time units):

>>> np.mean(service_times)

1.00249...

We can also check that mean wait agrees with the theoretical value of \(\frac{\rho}{\mu(1-\rho)}\) where \(\rho=\lambda/\mu\), with \(\lambda\), \(\mu\)) being the interarrival and service rates.

>>> lmbda = parameters['Arrival_distributions']['Class 0'][0][1]

>>> mu = parameters['Service_distributions']['Class 0'][0][1]

>>> rho = lmbda / mu

>>> np.mean(waits), rho / (mu * (1 - rho))

(1.0299..., 1.0)

Now that we have done this for a simple Markovian system let us create a number of distributions that all have the same mean service time and compare these:

>>> distributions = [

... ['Uniform', 0, 2], # A uniform distribution with mean 1

... ['Deterministic', 1], # A deterministic distribution with mean 1

... ['Triangular', 0, 2, 1], # A triangular distribution with mean 1

... ['Exponential', 1], # The Markovian distribution with mean 1

... ['Gamma', 0.91, 1.1], # A Gamma distribution with mean 1

... ['Lognormal', 0, .1], # A lognormal distribution with mean 1

... ['Weibull', 1.1, 3.9], # A Weibull distribuion with mean 1

... ['Empirical', [0] * 19 + [20]] # An empirical distribution with mean 1 (95% of the time: 0, 5% of the time: 20)

... ]

(More info can be found at the ciw documentation on distributions: ciw.readthedocs.io/en/latest/Features/distributions.html.)

Let us know simulate the queueing process for all the above distribution:

>>> columns = ["distribution", "waits", "service_times"]

>>> df = pd.DataFrame(columns=columns) # Create a dataframe that will keep all the data

>>> for distribution in distributions:

... parameters['Service_distributions']['Class 0'] = [distribution]

... waits, service_times = trials(parameters)

... n = len(waits)

... df = df.append(pd.DataFrame(list(zip([distribution[0]] * n, waits, service_times)), columns=columns))

If we look at the summary statistics we see that all distributions have the same mean service time but drastically different mean waiting times:

>>> bydistribution = df.groupby("distribution") # Grouping the data

>>> for name, df in sorted(bydistribution, key= lambda dist: dist[1].waits.max()):

... print("{}:\n\t Mean service time: {:.02f}\n\t Mean waiting time: {:.02f}\n\t 95% waiting time: {:.02f} \n\t Max waiting time: {:.02f}\n".format(

... name,

... df.service_times.mean(),

... df.waits.mean(),

... df.waits.quantile(0.95),

... df.waits.max()))

Deterministic:

Mean service time: 1.00

Mean waiting time: 0.51

95% waiting time: 2.11

Max waiting time: 6.73

Weibull:

Mean service time: 1.00

Mean waiting time: 0.54

95% waiting time: 2.24

Max waiting time: 8.16

Lognormal:

Mean service time: 1.01

Mean waiting time: 0.51

95% waiting time: 2.09

Max waiting time: 8.53

Triangular:

Mean service time: 1.00

Mean waiting time: 0.59

95% waiting time: 2.48

Max waiting time: 9.21

Uniform:

Mean service time: 1.00

Mean waiting time: 0.67

95% waiting time: 2.84

Max waiting time: 10.42

Exponential:

Mean service time: 1.00

Mean waiting time: 1.03

95% waiting time: 4.76

Max waiting time: 16.41

Gamma:

Mean service time: 1.00

Mean waiting time: 1.02

95% waiting time: 4.72

Max waiting time: 20.65

Empirical:

Mean service time: 0.99

Mean waiting time: 9.30

95% waiting time: 37.60

Max waiting time: 100.60

For example, the empirical distribution sees at least one individual waiting for a total of 100 time units! (Remember, individuals are arriving on average once every 2 time units and being served, on average every time unit!). Also 5% of individuals waited more than 37 time units in the empiral distribution but still for more conservative distributions 5% of individuals had waits larger than: 4.72 times units (Weibull), 4.76 time units (Exponential), 2.84 time units (Uniform) etc…

But just as we mentioned when looking at Anscombe’s quartet it’s important to not just look at summary statistics so here is some visualisation:

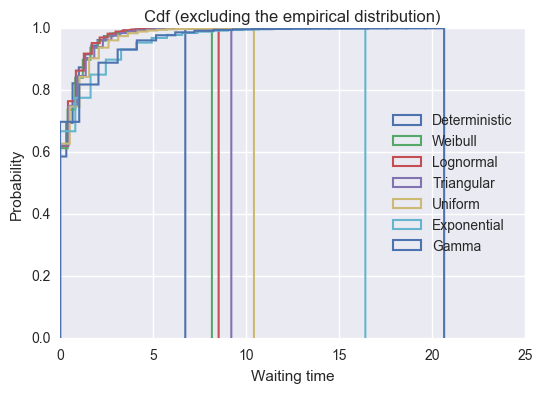

>>> for name, df in sorted(bydistribution, key= lambda dist: dist[1].waits.max())[:-1]:

... plt.hist(df.waits, normed=True, bins=20, cumulative=True,

... histtype = 'step', label=name, linewidth=1.5)

>>> plt.title("Cdf (excluding the empirical distribution)")

>>> plt.xlabel("Waiting time")

>>> plt.ylabel("Probability")

>>> plt.ylim(0, 1)

>>> plt.legend(loc=5);

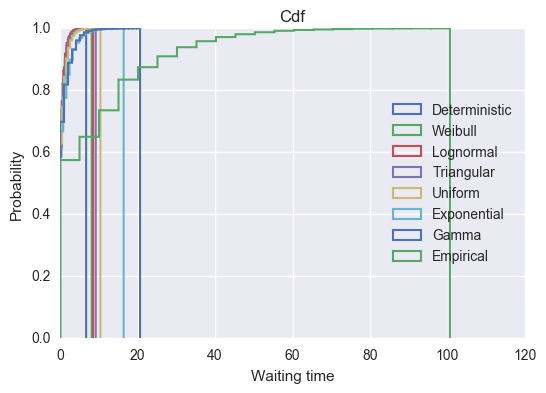

>>> for name, df in sorted(bydistribution, key= lambda dist: dist[1].waits.max()):

... plt.hist(df.waits, normed=True, bins=20, cumulative=True,

... histtype = 'step', label=name, linewidth=1.5)

>>> plt.title("Cdf")

>>> plt.xlabel("Waiting time")

>>> plt.ylabel("Probability")

>>> plt.ylim(0, 1)

>>> plt.legend(loc=5);

We see that the empirical distribution has by far the longest tail with some individuals having more than 80 time units spent waiting. Whilst this distribution is pretty artificial, it is fairly realistic to assume that there is a particular procedure or service that often takes no time at all but rarely does take a lot of more time. Examples of these will include healthcare operations where non routine procedures sometimes are needed.

This is all done with a pretty simple queueing system (just one server) but the Ciw python library makes it pretty easy to study more complex systems.

Side note

Ciw is already pretty well developed and has full 100% test coverage but is always looking for contributions (of any level) so please take a look at:

- The github repo: github.com/CiwPython/Ciw

- A talk given by Geraint Palmer describing the library and his research so far: youtube.com/watch?v=0_sIus0mPSM