On the worst play in superbowl history

In my last game theory class I gave students the choice between starting to rigorously look at extensive form games or to look at the last play of this years superbowl. No one objected to looking at the superbowl play (which has been called ‘the worst play in superbowl history’) as an opportunity to go over all the normal form game theory we have seen so far.

First of all I had to give a brief overview of American football so I drew a couple of pictures on the board, here is more or less what I drew:

I highlighted that the offensive team (the blue guys in my picture) can basically at any point do one of two things:

- Pass: the quarter back throws the ball down field. This works better when there is more room down the field for guys to get open but in general is a high risk high reward player.

- Run: the quarter back hands the ball to the running back. This in general ensures a small gain of yards and is less risky (but has less reward).

The defence can (at a very simplistic level) set up in two ways:

- Defend the pass: they might drop some of guys (red circles) ‘out of the box’ in a way as to cover blue guys trying to get open.

- Defend the run: they might drop more guys (red crosses) ‘in to the box’, leaving less people to cover the pass but having more people ready to stop the running back from gaining yards.

This immediately lets us set up (in a simplistic way) every phase of play in American Football as a two player normal form game where the Offense has strategy set: \(S_O=\{\text{P},\text{R}\}\) and the Defense has strategy set: \(S_D=\{\text{DP},\text{DR}\}\).

Now, to return to what is being called ‘the worst play in superbowl history’:

- The Seahawks have one of the best running backs in the game (funny interview of his here);

- They had the ball very close to the score line with downs (attempts) to spare.

Everyone seems to be saying that ‘not rushing’ was an idiotic thing to do. This article by the Economist explains things pretty well (including the back story), but in my class on Friday I thought I would go through the mathematics of it all.

First of all let us build some basic utilities (to be clear I am more or less pulling these out of a hat although I will carry out some Monte Carlo simulation at the end of this blog post).

- Let us assume (because Lynch is awesome) that on average running against a run defence would work 60% of the time;

- Running against a pass defence would work 98% of the time;

- Passing against a rush defence would work 90% of the time;

- Passing against a pass defence would work 50% of the time.

Our normal form game then looks like this (assuming that the game is zero sum):

If the Seahawks were 100% going to run the ball, in such a way as that the defence were in no doubt then the obvious best response is to use a rush defence (in reality this is actually what happened and the defensive player that was fairly isolated just made an amazing play). Then, the chance of the Seahawks scoring is 60%.

What does game theory say should happen?

First of all what should the offence do to ensure that the defense sometimes defends the pass? The theory tells us that the offence should make the defense indifferent. So let us assume that the offence runs \(x\) of the time so that the player is playing mixed strategy: \(\sigma_{\text{O}}=(x,1-x)\). The Nash equilibrium strategy for the offence would then obey the following equation:

the above corresponds to:

which has solution: \(x=20/30\approx.51\). So to make the defense indifferent, the offense should run only 51% of the time!

This in itself is not a Nash equilibria: we need to calculate the strategy that the defense should play so as to make the offense indifferent. We let \(\sigma_{\text{D}}=(y,1,y)\) and now need to solve:

the above corresponds to:

which has solution: \(y=8/13\approx.62\). So to make the offense indifferent, the defense should defend the run 62% of the time.

How good is the Nash equilibria?

We discussed earlier that if the offense passed with 0 probability (so in fact always ran in that situation) then the probability of scoring would be 60% (because the defense would know and just defend the run). The Nash equilibria we have calculated ensured that the play calling is balanced: which ‘keeps the defense honest’. What is the effect of this on offenses chances of scoring?

To find this out we can simply calculate the utility at the Nash equilibria. We can do this by calculating:

or because of the indifference ensured earlier we can just calculate:

So the Nash Equilibria makes things \(74.62/60\approx 1.24\) times better for the offense. Thus, in way, by picking a strategy in that particular instance that ended up not paying off, the offense ensured a larger long term chance of scoring in a similar situation.

Some sensitivity analysis

I have completely picked numbers more or less out of a hat. Thankfully we can combine the above analysis with some Monte Carlo simulation to see how much of an effect the assumptions have.

Let us consider the general form of our game as:

If the offense always runs then the expected chance of scoring is simply \(A\).

Let us make the following assumptions:

- Running against a pass defense is always better than running against a run defense: \(A<B\).

- Passing against a run defense is always better than passing against a pass defense: \(C>D\).

- Passing against a run defense is always better than running against a run defense: \(A<C\).

- Running against a pass defense is always better than passing against a pass defense: \(B>D\).

This simple set of assumptions ensures that no strategies are dominated for either player and so our Nash equilibria will be a mixed Nash equilibrium. Let us find the expected chance of scoring for the offence at the Nash equilibrium.

The defense will ensure that the offense is indifferent:

which is equivalent to:

This has solution:

(which thanks to our assumptions is indeed a probability distribution.)

Now thanks to this we can compute \(\alpha\) which will be some measure of how much better things are for the offense at the Nash equilibria (calculated as \(1.24\) earlier on).

which we can compute at Nash equilibrium as:

Monte carlo simulation

Now that that hard work is done let us write some very simple Python code that will randomly sample values for \(A,B,C,D\) according to our assumptions and then we can see what effect this has on \(alpha\).

Let us sample our input parameters according to the following:

- \(A \sim \mathcal{N} (60,10^2)\): normal distribution with mean 60 and standard deviation 10. Running against a run defense would work on average 60% of the time with a fair bit of variation.

- \(B \sim \mathcal{N} (95,5^2)\): normal distribution with mean 95 and standard deviation 5. Running against a pass defense works predictably well.

-

\(C \sim \mathcal{N} (85,15^2)\): normal distribution with mean 85 and standard deviation 15. Passing against a run defense works well but not robustly.

- \(D \sim \mathcal{N} (50,20^2)\): normal distribution with mean 50 and standard deviation 20. Passing against a pass defense does not well very well.

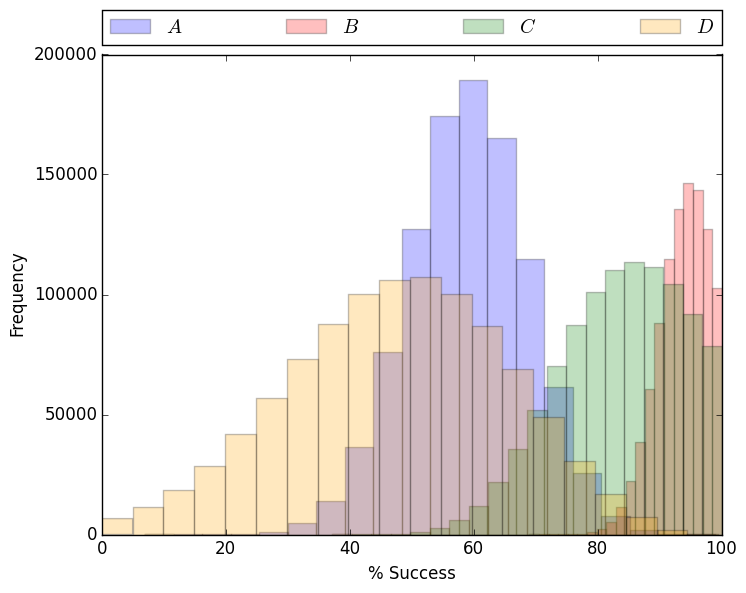

After sampling each parameter, a set of parameters is only accepted as valid if it follows the assumptions mentioned earlier (all the inequalities). Here is what the parameters look like after running 100000 simulations:

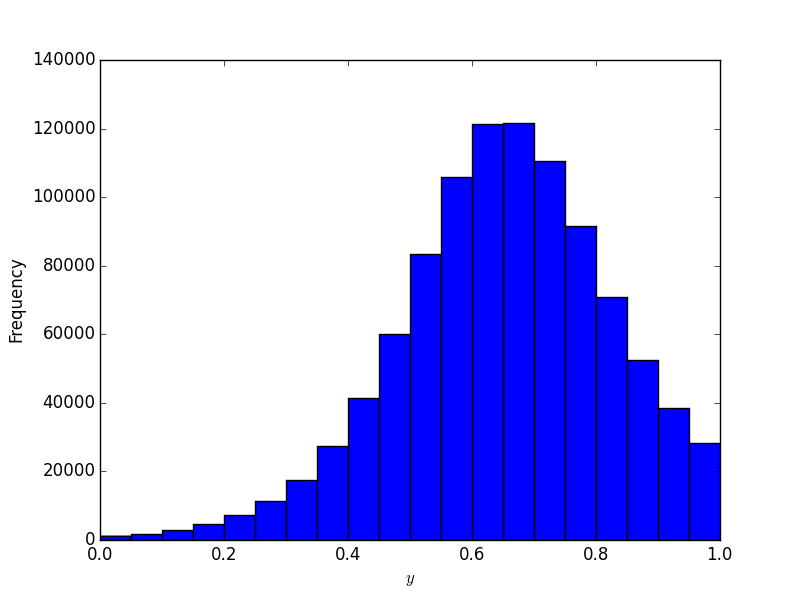

Now to look at some of the results. Here is what \(y\) looks like:

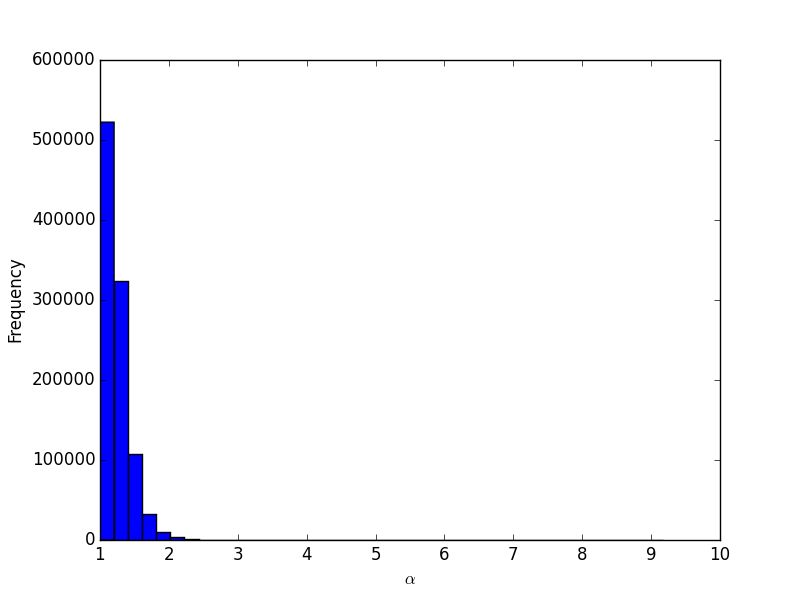

Recall that \(y\) is the probability with which the defense should defend the run. Finally, let us take a look at what \(\alpha\) looks like:

Recall that \(\alpha\) denotes the ratio of the scoring probability when the Nash equilibrium is played over the ‘just run all the time’. The graph is rather unhelpful as the tail is extremely long but there are some instances of our Monte Carlo simulation that have yielded a ten fold increase in scoring probability (this will occur when \(A\) is pretty low to begin with).

The mean ratio (based on our assumptions) is \(1.24\) and importantly the minimum is greater than \(1\).

All of this shows that even with a very broad relaxation of our assumptions it makes sense to at times run the ball. So game theory does in effect say that this was not ‘the worst play in super bowl history’ as it makes sense to at times pass in that situation.

TLDR: (Based on the assumptions) the coach who truly will at time pass in that situation will win the superbowl 24% more of the time than the coach who would only ever run.

Nonetheless this is ignoring a lot of the subtleties of the game itself, non more so than the fact the Patriots in fact came out in a run defense formation and the game was simply won by a great defensive play.

The code for all this can be found here.