Un peu de math

Describing a recent pre print and also pointing at the recognition it got for reproducibility.

A (very reproducible) paper about recognising zero determinant strategies

2019-04-03

In 2012, Press and Dyson published a paper that made quite a bit of noise in the Game Theoretic community. My favourite quote on the subject is from the MIT Technology review which claimed that "The world of game theory is currently on fire". In that paper, it was shown that a particular (simple) strategy could always do no worse than a given opponent. In this blog post I'll describe a preprint in which my authors and I describe a mathematical measure of how close any strategy is to acting this way but also describe some early recognition it has gotten, not for the results but for the reproducible nature of all the methodology.

Zero Determinant strategies

The particular strategy considered in Press and Dyson's is referred to as a memory one strategy due to the fact that it only uses one turn of memory to decide what it does next. In other words, even if an interaction between two agents has been taking place for a long time with a long history of interactions, it will only consider the last turn of which (in the Prisoners Dilemma) there are only four possibilities:

- Both agents cooperate;

- The player in question cooperates and the opponent defects;

- The player in question defects and the opponent cooperates;

- Both agents defect.

Thus, all strategies that only use the last turn of memory to decide what they do can be represented as a single vector: \(p\in[0, 1]_{\mathbb{R}}^4\) which maps the previous state to a probability of cooperating.

For example, the famous strategy Tit For Tat can be represented as:

\[ p = (1, 0, 1, 0) \]

What Press and Dyson did in their 2012 paper was show that given a match between two memory one players \(p, q\in[0, 1]_{\mathbb{R}}^4\) then one agent could force a linear relationship between the long run utilities of both agents (\(u_p, u_q\)). For the usual utility values of the Prisoner's Dilemma \(R, S, T, P\), if:

\[ (1 - p_1, 1 - p_2, p_3, p_4) = \alpha (R, S, T, P) + \beta (R, T, S, P) + \gamma \]

and

\[ \gamma = - P (\alpha + \beta) \]

then:

\[ u_p - P = \frac{-\beta}{\alpha} (u_q - P) \]

The important consideration here is that the only thing \(q\) can do to defend itself is to defect so that:

\[ u_p = u_q = P \]

Strategies that set this linear relationship are called Zero determinant strategies (because of the particular linear algebraic trick used to get the relationship).

The other result, that's in the appendix of their paper is that a single turn of memory is all that is required against a given opponent.

Recognising Zero Determinant strategies

The main result of our preprint which is available at arxiv.org/abs/1904.00973 is to invert this relationship, given a history of plays of any strategy, it is possible to empirically measure \(p\) and then compute a sum of squared errors of prediction (SSE) to see how far this empirical measure is from satisfying the above linear constraints.

Further to this, we use the Axelrod python library with over 204 strategies to see how the distribution of this measure is related to the evolutionary performance of strategies. Our main finding is that simple memory one strategies are not evolutionarily strong (even when they are zero determinant) because they cannot adapt to a variety of opponents. Indeed strategies with a high skew in their SSE distribution are most likely to be evolutionarily strong as they can indeed extort poor performers but work well with high performers.

This allowed us to include a cool quote by Darwin in the paper (hopefully the reviewers will agree):

"It is not the most intellectual of the species that survives; it is not the strongest that survives; but the species that survives is the one that is able to adapt to and to adjust best to the changing environment in which it finds itself."

The pre print is reproducible

One of the cool things about the work, more so than what it is, is how it was done.

First of all, it is of course all on github (and archived at zenodo): github.com/drvinceknight/testing_for_ZD.

Secondly you will see that the README includes a clean set of instruction of how to download the generated data (which is all archived at 10.5281/zenodo.1317619) and rerun all the analysis. In fact, thanks to the neat invoke python library you can recreate all results by running the following (from the cloned repo directory):

$ conda env create -f environment.yml

$ invoke data

$ invoke build

The source code for the various calculations is packaged in a Python packaged which is all automatically tested. This implies that anyone can use the developed methodology on their own data with as little friction as possible.

Each specific figure, table and in some cases number is all in it's own subdirectory with the source code to create it.

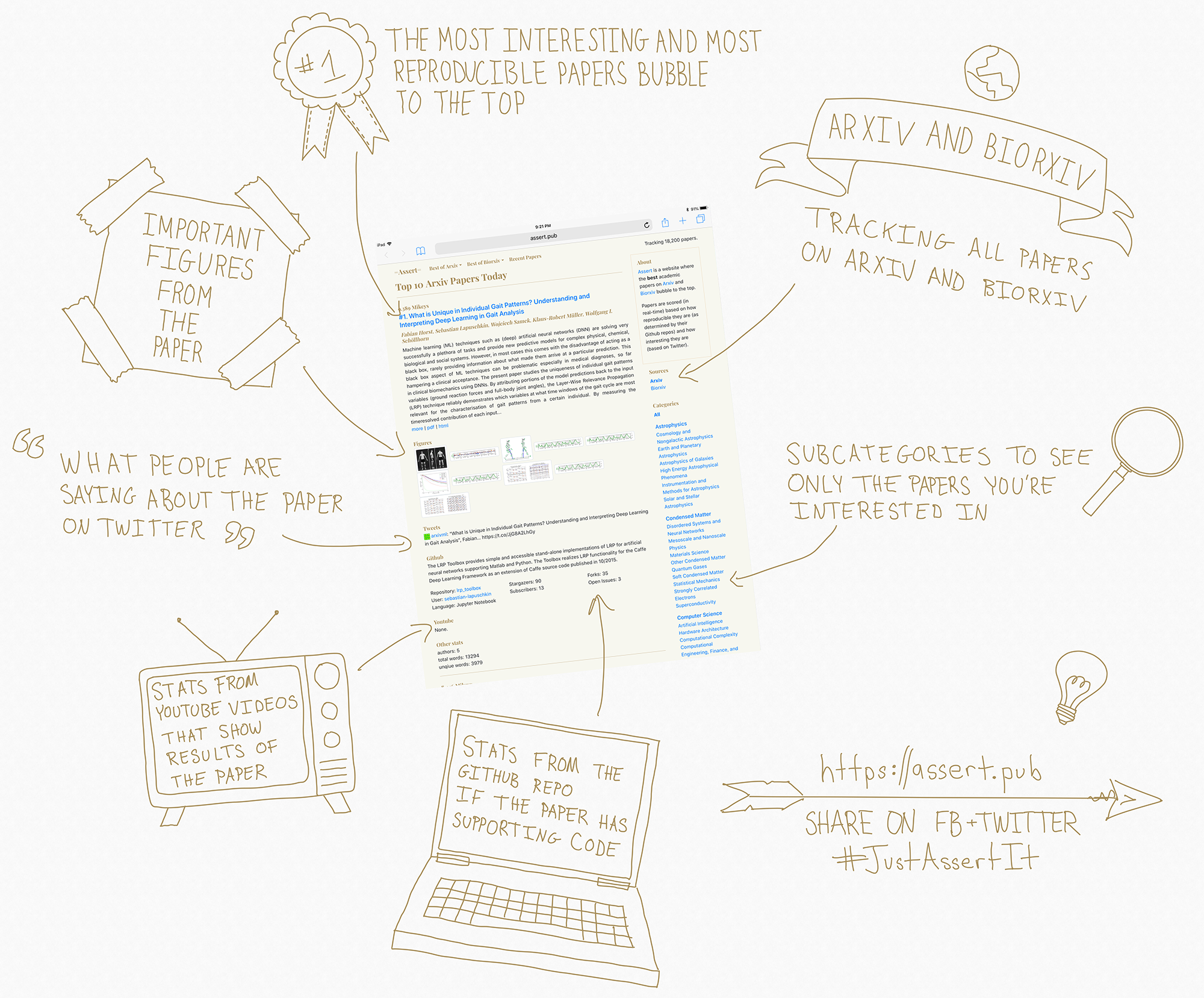

As a result of putting this preprint on the arxiv, the following morning my co-authors and I got notified via a tweet (FYI, they got my handle wrong but nbd :)) that a service called "assert" was featuring our paper as an example of reproducible research: http://assert.pub/papers/1904.00973.

The description from their twitter bio:

Papers are scored in real-time based on how reproducible they are (based on their Github repos) and how interesting they are (based on Twitter).

Here's an image (from their twitter account) that shows what assert does:

It looks like a clever service and one to keep an eye on:

A blog about programming (usually scientific python), mathematics (usually game theory) and learning (usually student centred pedagogic approaches).

Source code: drvinceknight Twitter: @drvinceknight Email: [email protected] Powered by: Python mathjax highlight.js Github pages Bootstrap