Chapter 15 - Matching games

Recap

In the previous chapter:

- We defined stochastic games;

- We investigated approached to obtaining Markov strategy Nash equilibria.

In this chapter we will take a look at a very different type of game.

Matching Games

Consider the following situation:

“In a population of \(N\) suitors and \(N\) reviewers. We allow the suitors and reviewers to rank their preferences and are now trying to match the suitors and reviewers in such a way as that every matching is stable.”

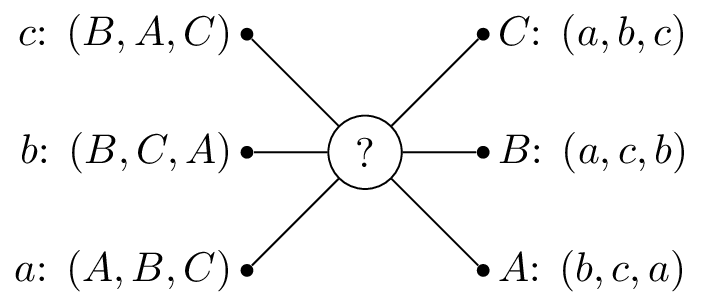

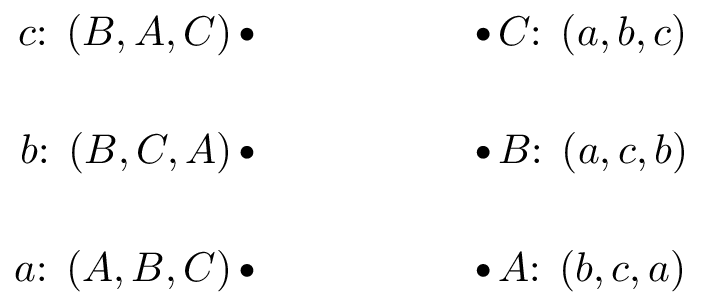

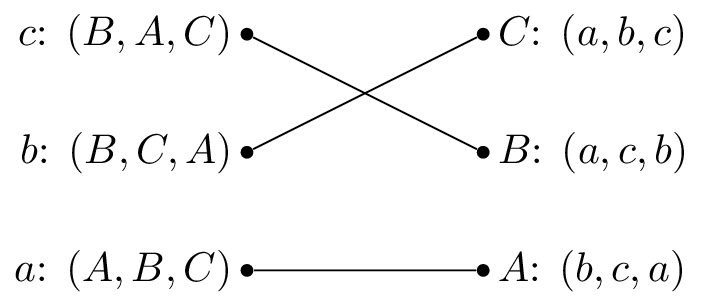

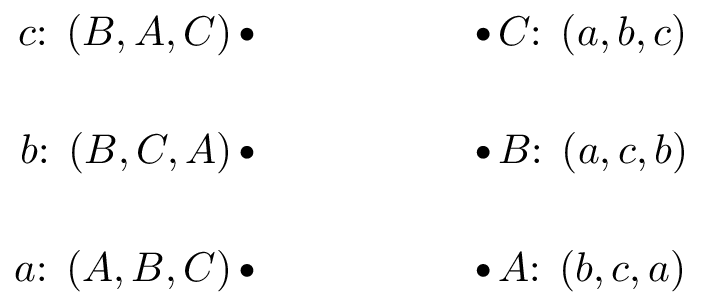

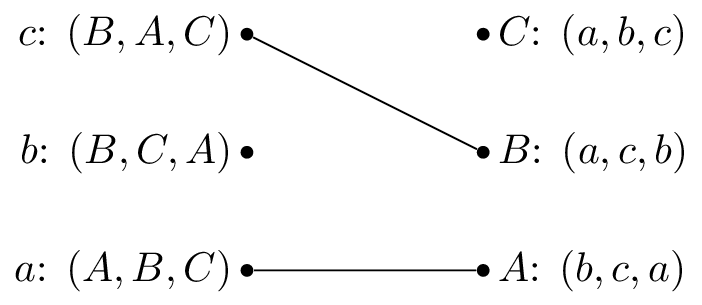

If we consider the following example with suitors: \(S=\{a,b,c\}\) and reviewers: \(R=\{A,B,C\}\) with preferences shown.

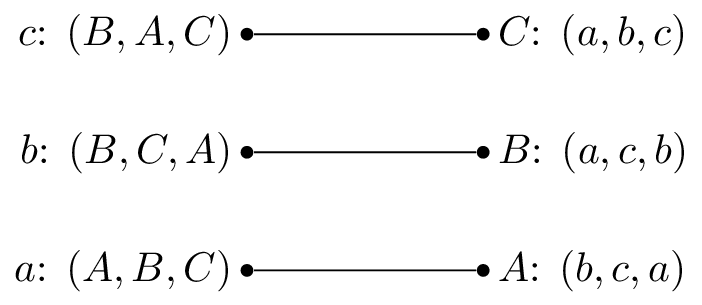

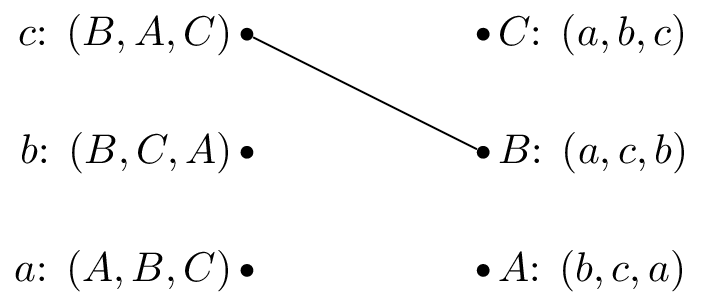

So that \(A\) would prefer to be matched with \(b\), then \(c\) and lastly \(c\). One possible matching would be is shown.

In this situation, \(a\) and \(b\) are getting their first choice and \(c\) their second choice. However \(B\) actually prefers \(c\) so that matching is unstable.

Let us write down some formal definitions:

Definition of a matching game

A matching game of size \(N\) is defined by two disjoint sets \(S\) and \(R\) or suitors and reviewers of size \(N\). Associated to each element of \(S\) and \(R\) is a preference list:

A matching \(M\) is a any bijection between \(S\) and \(R\). If \(s\in S\) and \(r\in R\) are matched by \(M\) we denote:

Definition of a blocking pair

A pair \((s,r)\) is said to block a matching \(M\) if \(M(s)\ne r\) but \(s\) prefers \(r\) to \(M(s)\) and \(r\) prefers \(s\) to \(M^{-1}(r)\).

In our previous example \((c,B)\) blocks the proposed matching.

Definition of a stable matching

A matching \(M\) with no blocking pair is said to be stable.

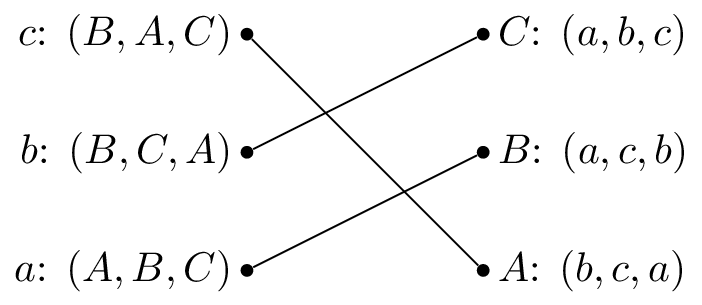

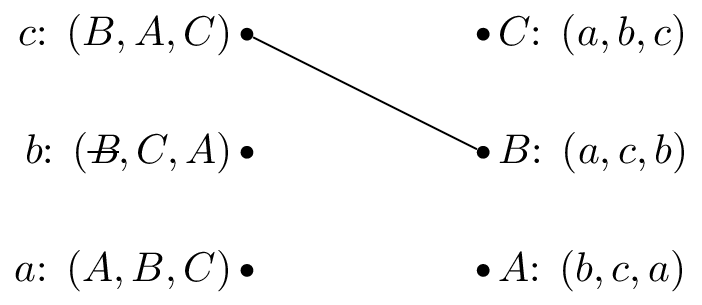

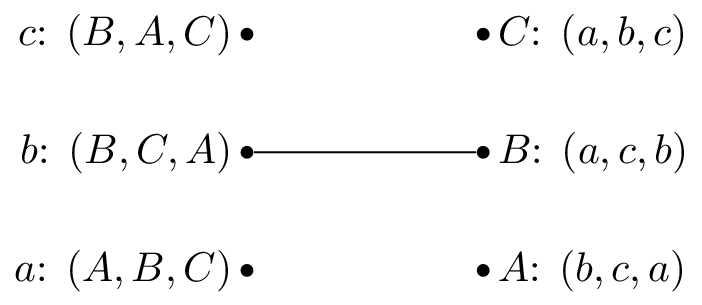

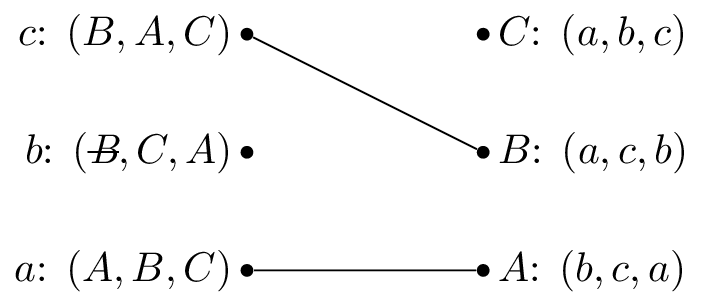

A stable matching is shown.

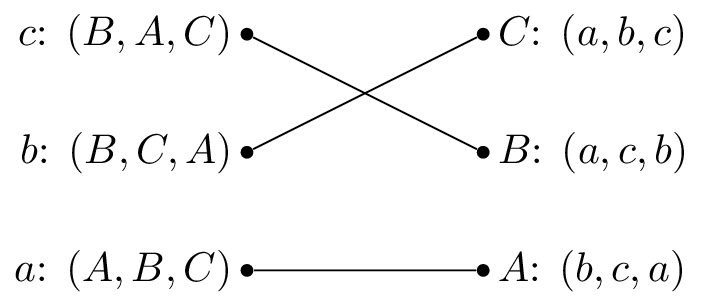

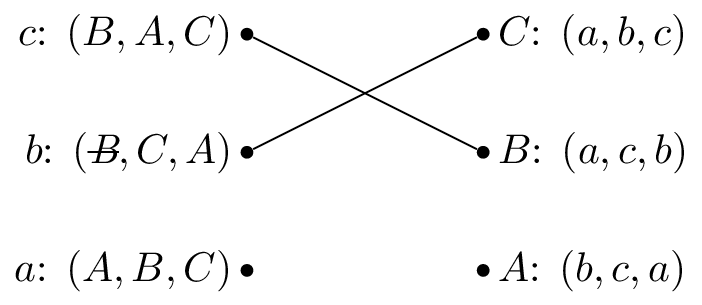

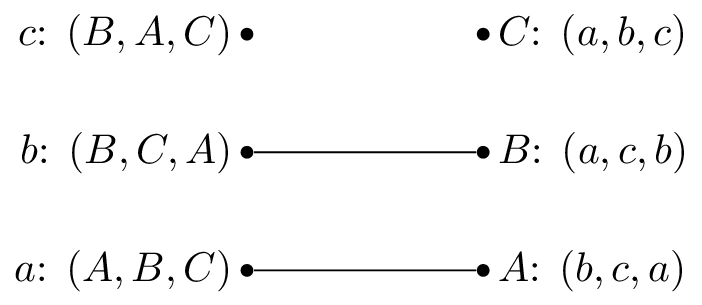

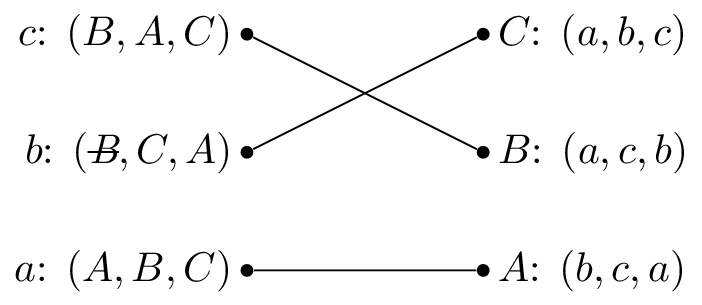

The stable matching is not unique, the matching shown is also stable:

The Gale-Shapley Algorithm

Here is the Gale-Shapley algorithm, which gives a stable matching for a matching game:

- Assign every \(s\in S\) and \(r\in R\) to be unmatched

- Pick some unmatched \(s\in S\), let \(r\) be the top of \(s\)’s preference list:

- If \(r\) is unmatched set \(M(s)=r\)

- If \(r\) is matched:

- If \(r\) prefers \(s\) to \(M^{-1}(r)\) then set \(M(r)=s\)

- Otherwise \(s\) remains unmatched and remove \(r\) from \(s\)’s preference list.

- Repeat step 2 until all \(s\in S\) are matched.

Let us illustrate this algorithm with the above example.

We pick \(c\) and as all the reviewers are unmatched set \(M(c)=B\).

We pick \(b\) and as \(B\) is matched but prefers \(c\) to \(b\) we cross out \(B\) from \(b\)’s preferences.

We pick \(b\) again and set \(M(b)=C\).

We pick \(a\) and set \(M(a)=A\).

Let us repeat the algorithm but pick \(b\) as our first suitor.

We pick \(b\) and as all the reviewers are unmatched set \(M(b)=B\).

We pick \(a\) and as \(A\) is unmatched set \(M(a)=A\).

We pick \(c\) and \(b\) is matched but prefers \(c\) to \(M^{-1}(B)=b\), we set \(M(c)=B\).

We pick \(b\) and as \(B\) is matched but prefers \(c\) to \(b\) we cross out \(B\) from \(b\)’s preferences:

We pick \(b\) again and set \(M(b)=C\).

Both these have given the same matching.

Theorem guaranteeing a unique matching as output of the Gale Shapley algorithm.

All possible executions of the Gale-Shapley algorithm yield the same stable matching and in this stable matching every suitor has the best possible partner in any stable matching.

Proof

Suppose that an arbitrary execution \(\alpha\) of the algorithm gives \(M\) and that another execution \(\beta\) gives \(M’\) such that \(\exists\) \(s\in S\) such that \(s\) prefers \(r’=M’(s)\) to \(r=M(s)\).

Without loss of generality this implies that during \(\alpha\) \(r’\) must have rejected \(s\). Suppose, again without loss of generality that this was the first occasion that a rejection occured during \(\alpha\) and assume that this rejection occurred because \(r’=M(s’)\). This implies that \(s’\) has no stable match that is higher in \(s’\)’s preference list than \(r’\) (as we have assumed that this is the first rejection).

Thus \(s’\) prefers \(r’\) to \(M’(s’)\) so that \((s’,r’)\) blocks \(M’\). Each suitor is therefore matched in \(M\) with his favorite stable reviewer and since \(\alpha\) was arbitrary it follows that all possible executions give the same matching.

We call a matching obtained from the Gale Shapley algorithm suitor-optimal because of the previous theorem. The next theorem shows another important property of the algorithm.

Theorem of reviewer sub optimality

In a suitor-optimal stable matching each reviewer has the worst possible matching.

Proof

Assume that the result is not true. Let \(M_0\) be a suitor-optimal matching and assume that there is a stable matching \(M’\) such that \(\exists\) \(r\) such that \(r\) prefers \(s=M_0^{-1}(r)\) to \(s’=M’^{-1}(r)\). This implies that \((r,s)\) blocks \(M’\) unless \(s\) prefers \(M’(s)\) to \(M_0(s)\) which contradicts the fact the \(s\) has no stable match that they prefer in \(M_0\).