Chapter 14 - Stochastic games

Recap

In the previous chapter:

- We considered games of incomplete information;

- Discussed some basic utility theory;

- Considered the principal agent game.

In this chapter we will take a look at a more general type of random game.

Stochastic games

Definition of a stochastic game

A stochastic game is defined by:

- X a set of states with a stage game defined for each state;

- A set of strategies \(S_i(x)\) for each player for each state \(x\in X\);

- A set of rewards dependant on the state and the actions of the other players: \(u_i(x,s_1,s_2)\);

- A set of probabilities of transitioning to a future state: \(\pi(x’|x,s_1,s_2)\);

- Each stage game is played at a set of discrete times \(t\).

We will make some simplifying assumptions in this course:

- The length of the game is not known (infinite horizon) - so we use discounting;

- The rewards and transition probabilities are not dependent;

- We will only consider strategies called Markov strategies.

Definition of a Markov strategy

A strategy is call a Markov strategy if the behaviour dictated is not time dependent.

Example

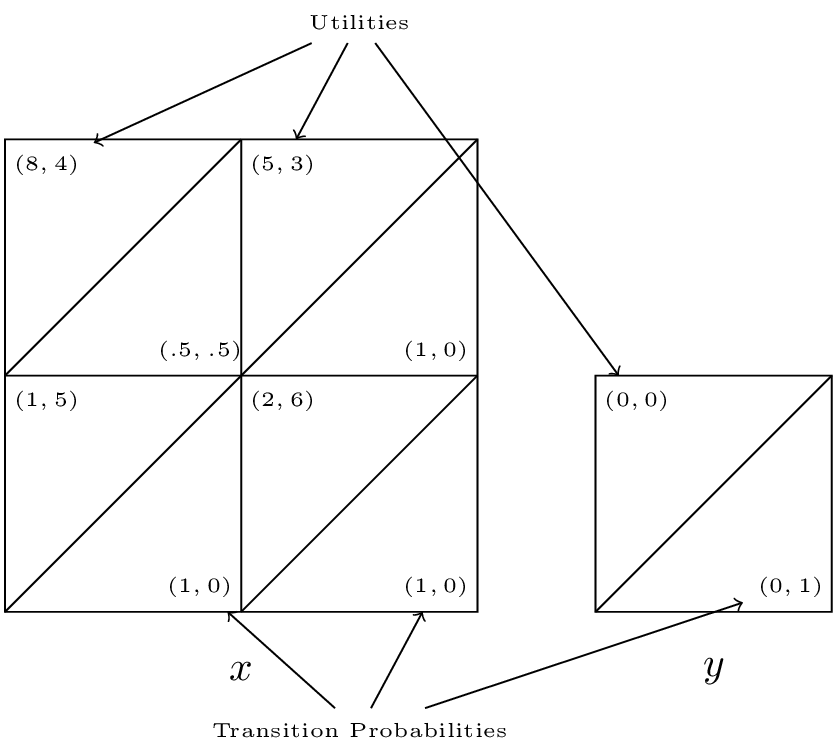

Consider the following game with \(X=\{x,y\}\):

- \(S_1(x)=\{a,b\}\) and \(S_2(x)=\{c,d\}\);

- \(S_1(y)=\{e\}\) and \(S_2(x)=\{f\}\);

We have the stage game corresponding to state \(x\):

The stage game corresponding to state \(y\):

The transition probabilities corresponding to state \(x\):

The transition probabilities corresponding to state \(y\):

A concise way of representing all this is shown.

We see that the Nash equilibrium for the stage game corresponding to \(x\) is \((a, c)\) however as soon as the players play that strategy profile they will potentially go to state \(y\) which is an absorbing state at which players gain no further utility.

To calculate utilities for players in infinite horizon stochastic games we use a discount rate. Thus without loss of generality if the game is in state \(x\) and we assume that both players are playing \(\sigma^*_i\) then player 1 would be attempting to maximise future payoffs:

where \(U_1^*\) denotes the expected utility to player 1 when both players are playing the Nash strategy profile.

Thus a Nash equilibrium satisfies:

Solving these equations is not straightforward. We will take a look at one approach by solving the example we have above.

Finding equilibria in stochastic games

Let us find a Nash equilibrium for the game considered above with \(\delta=2/3\).

State \(y\) gives no value to either player so we only need to consider state \(x\). Let the future gains to player 1 in state \(x\) be \(v\), and the future gains to player 2 in state \(x\) be \(u\). Thus the players are facing the following game:

We consider each strategy pair and state the condition for Nash equilibrium:

- \((a,c)\): \(v\leq 21\) and \(u\leq 3\).

- \((a,d)\): \(u\geq3\).

- \((b,c)\): \(v\geq 21\) and \(5\geq 6\).

- \((b,d)\): \(5\leq2\).

Now consider the implications of each of those profiles being an equilibrium:

- \(8+v/3=v\) \(\Rightarrow\) \(v=12\) and \(4+u/3=u\) \(\Rightarrow\) \(u=6\) which contradicts the corresponding inequality.

- \(3+2u/3=u\) \(\Rightarrow\) \(u=9\).

- The second inequality cannot hold.

- The inequality cannot hold.

Thus the unique Markov strategy Nash equilibria is \((a,d)\) which is not the stage Nash equilibria!