Chapter 10 - Infinitely Repeated Games

Recap

In the previous chapter:

- We defined repeated games;

- We showed that a sequence of stage Nash games would give a subgame perfect equilibria;

- We considered a game, illustrating how to identify equilibria that are not a sequence of stage Nash profiles.

In this chapter we’ll take a look at what happens when games are repeatedly infinitely.

Discounting

To illustrate infinitely repeated games (\(T\to\infty\)) we will consider a Prisoners dilemma as our stage game.

Let us denote \(s_{C}\) as the strategy “cooperate at every stage”. Let us denote \(s_{D}\) as the strategy “defect at every stage”.

If we assume that both players play \(s_{C}\) their utility would be:

Similarly:

It is impossible to compare these two strategies. To be able to carry out analysis of strategies in infinitely repeated games we make use of a discounting factor \(0<\delta<1\).

The interpretation of \(\delta\) is that there is less importance given to future payoffs. One way of thinking about this is that “the probability of recieveing the future payoffs decreases with time”.

In this case we write the utility in an infinitely repeated game as:

Thus:

and:

Conditions for cooperation in Prisoner’s Dilemmas

Let us consider the “Grudger” strategy (which we denote \(s_G\)):

“Start by cooperating until your opponent defects at which point defect in all future stages.”

If both players play \(s_G\) we have \(s_G=s_C\):

If we assume that \(S_1=S_2=\{s_C,s_D,s_G\}\) and player 2 deviates from \(S_G\) at the first stage to \(s_D\) we get:

Deviation from \(s_G\) to \(s_D\) is rational if and only if:

thus if \(\delta\) is large enough \((s_G,s_G)\) is a Nash equilibrium.

Importantly \((s_G,s_G)\) is not a subgame perfect Nash equilibrium. Consider the subgame following \((r_1,c_2)\) having been played in the first stage of the game. Assume that player 1 adhers to \(s_G\):

-

If player 2 also plays \(s_G\) then the first stage of the subgame will be \((r_2,c_1)\) (player 1 punishes while player 2 sticks with \(c_1\) as player 1 played \(r_1\) in previous stage). All subsequent plays will be \((r_2,c_2)\) so player 2’s utility will be:

-

If player 2 deviates from \(s_G\) and chooses to play \(D\) in every period of the subgame then player 2’s utility will be:

which is a rational deviation (as \(0<\delta<1\)).

Two questions arise:

- Can we always find a strategy in a repeated game that gives us a better outcome than simply repeating the stage Nash equilibria? (Like \(s_G\))

- Can we also find a strategy with the above property that in fact is subgame perfect? (Unlike \(s_G\))

Folk theorem

The answer is yes! To prove this we need to define a couple of things.

Definition of an average payoff

If we interpret \(\delta\) as the probability of the repeated game not ending then the average length of the game is:

We can use this to define the average payoffs per stage:

This average payoff is a tool that allows us to compare the payoffs in an infitely repeated game to the payoff in a single stage game.

Definition of individually rational payoffs

Individually rational payoffs are average payoffs that exceed the stage game Nash equilibrium payoffs for both players.

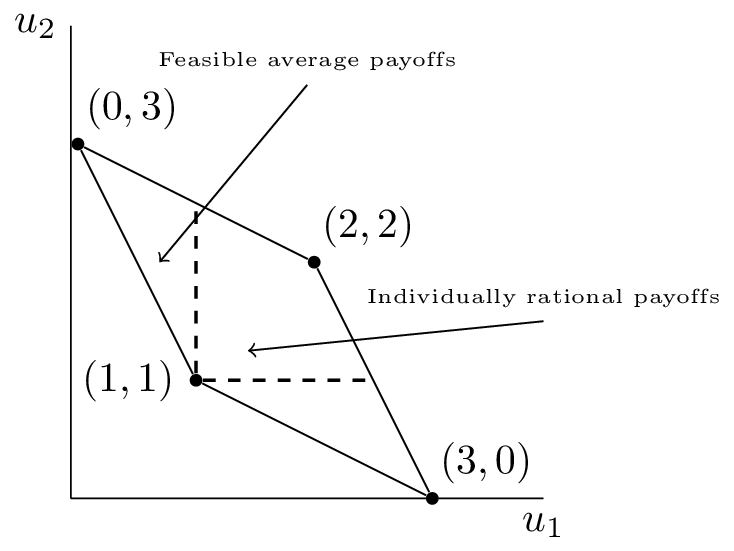

As an example consider the plot corresponding to a repeated Prisoner’s Dilemma.

The feasible average payoffs correspond to the feasible payoffs in the stage game. The individually rational payoffs show the payoffs that are better for both players than the stage Nash equilibrium.

The following theorem states that we can choose a particular discount rate that for which there exists a subgame perfect Nash equilibrium that would give any individually rational payoff pair!

Folk Theorem for infinitely repeated games

Let \((u_1^*,u_2^*)\) be a pair of Nash equilibrium payoffs for a stage game. For every individually rational pair \((v_1,v_2)\) there exists \(\bar \delta\) such that for all \(1>\delta>\bar \delta>0\) there is a subgame perfect Nash equilibrium with payoffs \((v_1,v_2)\).

Proof

Let \((\sigma_1^*,\sigma_2^*)\) be the stage Nash profile that yields \((u_1^*,u_2^*)\). Now assume that playing \(\bar\sigma_1\in\Delta S_1\) and \(\bar\sigma_2\in\Delta S_2\) in every stage gives \((v_1,v_2)\) (an individual rational payoff pair).

Consider the following strategy:

“Begin by using \(\bar \sigma_i\) and continue to use \(\bar \sigma_i\) as long as both players use the agreed strategies. If any player deviates: use \(\sigma_i^*\) for all future stages.”

We begin by proving that the above is a Nash equilibrium.

Without loss of generality if player 1 deviates to \(\sigma_1’\in\Delta S_1\) such that \(u_1(\sigma_1’,\bar \sigma_2)>v_1\) in stage \(k\) then:

Recalling that player 1 would receive \(v_1\) in every stage with no devitation, the biggest gain to be made from deviating is if player 1 deviates in the first stage (all future gains are more heavily discounted). Thus if we can find \(\bar\delta\) such that \(\delta>\bar\delta\) implies that \(U_1^{(1)}\leq \frac{v_1}{1-\delta}\) then player 1 has no incentive to deviate.

as \(u_1(\sigma_1’,\bar \sigma_2)>v_1>u_1^*\), taking \(\bar\delta=\frac{u_1(\sigma_1’,\bar\sigma_2)-v_1}{u_1(\sigma_1’,\bar\sigma_2)-u_1^*}\) gives the required required result for player 1 and repeating the argument for player 2 completes the proof of the fact that the prescribed strategy is a Nash equilibrium.

By construction this strategy is also a subgame perfect Nash equilibrium. Given any history both players will act in the same way and no player will have an incentive to deviate:

- If we consider a subgame just after any player has deviated from \(\bar\sigma_i\) then both players use \(\sigma_i^*\).

- If we consider a subgame just after no player has deviated from \(\bar\sigma_i\) then both players continue to use \(\bar\sigma_i\).